“This school turns us into robots — going page by page, doing the routine.” –Eve, high school junior

Douglas, high school senior

“Understanding what is going on in our lives — what we’re going through — would improve how much and what kind of work [our teachers] give us. It would relieve a lot of stress.”

A feeling of belonging in school goes hand in hand with students’ engagement in learning.

Eve and Douglas, and many middle and high school students like them, tell us that they feel like “robo-students,” mindlessly “doing school.” They go through the motions of completing their schoolwork, but they don’t find value in their assignments, nor do they feel known as individual humans in their schools. We know that when students find meaning in what they are studying — when they are not just working for the sake of a grade or to check off an assignment on a to-do list — they are more likely to be academically successful. We also know that all students need to feel cared for and respected to thrive in school. So how can we as educators truly engage our students in work that they find meaningful and valuable? How can we make school a place where students feel valued, connected, and included?

Our research at Challenge Success, a nonprofit school reform organization affiliated with Stanford University’s Graduate School of Education, shows that the answers to these questions are related to specific practices that make classroom lessons more relevant, fair, and useful while promoting a schoolwide climate of care and belonging. In other words, the classroom curriculum and lessons affect not only students’ academic trajectory but also their social and emotional outcomes.

We have known for years that social, emotional, and cognitive processing are all neurologically intertwined. When students of all ages and stages feel they belong to a community, they are more likely to thrive — and students don’t learn as much when they feel uncertain about their belonging. These conclusions don’t apply to just a select few; they cross income levels, ethnic and racial backgrounds, geographic differences, and gender identities (Furrer & Skinner, 2003; Gillen-O’Neel & Fuligni, 2014; Gray, Hope, & Matthews, 2018; Healey & Stroman, 2021; Osterman, 2000). In a recent Challenge Success study, we found further evidence of the significant association between high school students’ experience of academic engagement and their sense of belonging. This association was greatest when schools and teachers engaged in specific practices: In short, when teachers intentionally design lessons that are meaningful to their students, build an authentic climate of respect into their classrooms, listen closely to students and incorporate their input, and grade in a way that students consider fair, students’ sense of belonging and academic engagement are more likely to be high.

Measuring engagement and belonging

From 2018 to 2020, we surveyed approximately 55,000 public (60%) and private (40%) high school students from 73 schools across the country. About half of the high school students in this study identify as girls or women (49%) and half identify as boys or men (48%). The remaining 3% identify as gender non-binary or “unsure.” Approximately 45% of the high school students identified as white; 18% East Asian, Asian, or Asian American; 12% Latinx; 9% multiracial or multiethnic; 6% South Asian or Indian; 4% Black or African American; 2% Pacific Islander; and 4% “Other.” Most schools in this study are well-resourced and located in urban or suburban areas of the country.

The survey included questions related to the affective, behavioral, and cognitive dimensions (or the ABCs) of student engagement (adapted from Marks, 2000). The affective scale evaluates students’ level of interest in and enjoyment of schoolwork through questions such as, “How often do you find your schoolwork interesting?” The behavioral scale gauges students’ effort, hard work, mental exertion, and assignment completion with questions like, “How often do you try as hard as you can in school?” and “How often do you pay attention in your classes?” And the cognitive scale measures students’ attitudes toward their schoolwork and the perceptions of its value and importance by asking such questions as, “How often do you find your schoolwork meaningful?”

Some students may be disengaged in all three dimensions (approximately 10% of our sample). But many were engaged in just one or two dimensions. Students like Eve, for example, who said she feels like a robot at school, may score high on the behavioral scale of engagement: They typically attend classes and turn in their assignments, but they may not find joy in the process, and they rarely find meaning and value in their schoolwork. This behavior, which we call “doing school,” characterized 48% of our sample. Other students (26% of the sample) score high on cognitive and behavioral dimensions of engagement, but do not enjoy the work or find it interesting, while only 13% of the students are fully engaged in all three dimensions — cognitive, affective, and behavioral.

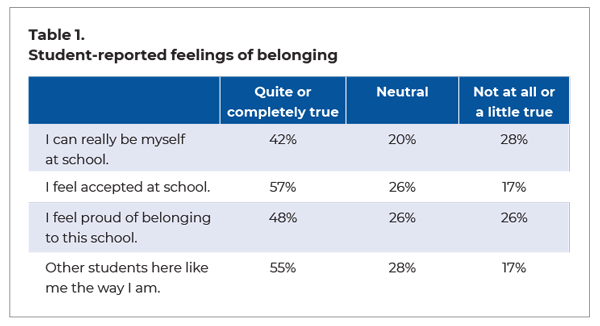

In addition to asking students questions about their engagement in school, we sought to determine their sense of belonging by asking a series of questions about the extent to which they felt respected, valued, cared about, and known by their teachers and peers in school. Using a reliable and valid scale adapted from Carol Goodenow’s (1993) Psychological Sense of School Membership Scale, we asked students to what extent they agreed with these statements:

- I can really be myself at this school.

- I feel accepted at this school.

- I feel proud of belonging to this school.

- Other students here like me the way that I am.

Across all of the above items, more students reported a sense of belonging at their school than did not; however, it is worth noting that, depending on the item, from 17% to 28% (7,600 to 14,000 students) of students responded that they did not feel a sense of belonging (See Table 1).

By combining our findings from the engagement questions with the belonging questions, we found that students who are fully engaged (scoring high on behavioral, cognitive, and affective engagement) are also more likely to feel a strong sense of belonging in school. This association between belonging and engagement is bidirectional, meaning that students’ sense of belonging in school is also significantly positively correlated with feeling engaged in their schoolwork. We find that cognitive engagement, in particular, accounts for a significant amount of the correlation between belonging and engagement.

Putting it into practice

Because of the bidirectional nature of the relationship between engagement and belonging, we cannot say that one condition comes first and leads to the other — only that they tend to go together. So when we work with schools to transform the student experience into one that is more engaging, inclusive, and equitable, we often say that it doesn’t matter if they start with a focus on engagement or on belonging. Improvements in one area are likely to correlate with improvement in the other. Furthermore, our research, and that of others (e.g., Gray, Hope, & Matthews, 2018; Healey & Stroman, 2021), reveals that the same educator behaviors and strategies that are highly effective for improving student engagement also help create more caring and inclusive communities where students feel they belong. We believe that these strategies can benefit all students but may be especially beneficial in secondary schools, where students have multiple teachers who have less time to get to know them well during the course of a school day.

Value student ideas and promote student agency. Students experience the curriculum firsthand, so they often know best how to make school more engaging and inclusive. Regularly ask students to weigh in on assignments and ways to improve classroom policies and practices. Make a special effort to invite students to the conversation who don’t typically speak up, and offer a variety of different kinds of listening opportunities for students to participate in. For instance, educators may want to convene small focus groups of students, host a fishbowl conversation, or conduct an “I Wish” campaign that invites students to anonymously voice their hopes and ideas for improving the learning environment.

Create a climate of mutual respect. With our country divided in so many ways, it can be challenging for educators to foster a caring and inclusive space for productive dialogue. Students need to know that their opinions will be respected, even when they differ from those of their teachers or peers. Strengthen student-teacher relationships and peer relationships by providing formal and informal opportunities for students and teachers to get to know one another. Teachers can start to build trust and buy-in by offering frequent icebreakers, check-in questions, and “reverse office hours” where teachers sign up students for one-on-one meetings. Educators can also integrate more peer collaboration activities, model and practice positive classroom communication and conflict resolution strategies, and regularly check in with students who may feel marginalized. A climate of trust and care will help when conflicts do arise, and certain practices such as restorative justice and peacemaking circles offer structured ways to engage in dialogue and resolve problems.

Design lessons that are meaningful for students and deepen their understanding. Students may think of a task as busywork when they do not understand the reasoning behind it, leading them to cognitively disengage, even if they complete the assignment. Be sure that every assignment has a clear purpose and clarify that purpose for students by showing them how the skills they are learning can be immediately applied outside the classroom. Try to connect activities and lessons to students’ backgrounds, interests, and prior knowledge and, when possible, encourage them to engage in authentic projects with real-world implications. In addition, strive to choose topics and content that reflect the cultures and experiences of the students in your school. When students see themselves reflected in the curriculum and find ways to productively apply this knowledge within their communities, they are more likely to feel included and engaged. Ideally, a curriculum will provide “mirrors” for students to see themselves and “windows” to help them see the lives and experiences of others (Bishop, 1990).

Use grading practices that students perceive as fair and supportive. Set high standards for students, be clear and explicit about those standards, and communicate to students that they belong in your classroom and they can succeed at meeting those standards. Too often, students see low grades as indicators that they don’t measure up and that they will never be successful. If students are having trouble, let them know that you have confidence in them and provide resources as well as concrete suggestions for how they can improve. If a student hasn’t demonstrated mastery of a concept, they may feel that the problem is within them, a feeling that can threaten their feeling of belonging. Encouraging students to revise and try again sends a message to students that their performance in one particular moment isn’t a reflection of their intellect; it simply means they need more time and support to reach the end goal. Also keep in mind that not all students are comfortable asking for help or advocating for themselves. Proactively reach out to these students and invite them to meet with you to help them develop the skills they need.

Lose the “gotcha” in assessments. Many students report in our surveys that high-stakes assessments and pressure to get good grades can be a source of undue stress. While competition as a team can promote a sense of belonging, individual competition and rankings based on grades can undermine students’ sense of belonging and reduce their motivation. Although many families have received the message that coming out on top in the competition for good grades and admission to the best colleges is essential to long-term success, our research has shown that there are many paths to success that don’t require getting into a top college (Challenge Success, 2018). Assessments that are designed not to rank or sort students but, rather, to measure what they know and are able to do can build students’ sense of competency, which fosters motivation and engagement. Try open-note or open-book assessments to lower students’ anxiety. (Remember that in the real world, you almost never have to show what you know during a timed assessment and without access to resources such as computers and coworkers.) Help students become more comfortable with assessment by conducting more frequent, untimed, low-stakes, or ungraded formative assessments that help you and your students see what they have learned and are able to do and where they may need more practice.

Lessons for students, not robots

When students are disengaged, they may robotically complete and turn in assignments, but they are less likely to retain information and learn more deeply. By implementing strategies that build on students’ own competencies, identities, and experiences, educators not only foster meaningful cognitive engagement but also influence students’ sense that they belong in the classroom and school.

Robots may not have a need to feel included in society, but every student needs to feel like they are seen and valued in order to learn. Engaging with lessons that are useful and relevant helps students to feel excited about and included in the learning process and respected for who they are and what they can contribute. Creating a culture where belonging and engagement in learning are foundational is a win for all of us, students and educators alike.

If you want to learn more about Reach partnership with Challenge Success click here!

References:

Bishop, R.S. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives, 6 (3), ix–xi.

Challenge Success. (2018, October). A ‘fit’ over rankings: Why college engagement matters more than selectivity. Author.

Furrer, C. & Skinner, E. (2003). Sense of relatedness as a factor in children’s academic engagement and performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95, 148-162.

Gillen-O’Neel, C. & Fuligni, A. (2014). A longitudinal study of school belonging and academic motivation across high school. Child Development, 84 (2), 678-692.

Goodenow, C. (1993). The psychological sense of school membership among adolescents: Scale development and educational correlates. Psychology in the Schools, 30 (1), 79-90.

Gray, D.L., Hope, E.C., & Matthews, J.S. (2018). Black and belonging at school: A case for interpersonal, instructional, and institutional opportunity structures. Educational Psychologist, 53 (2), 97-113.

Healey, K. & Stroman, C. (2021). Structures for belonging: A synthesis of research on belonging — Supportive learning environments. Student Experience Research Network.

Marks, H. (2000). Student engagement in instructional activity: Patterns in the elementary, middle, and high school years. American Educational Research Journal, 37 (1), 153-184.

Osterman, K. (2000). Students’ need for belonging in the school community. Review of Educational Research, 70 (3), 323-367.

Walton, G. (2021, November 9). Stop telling students, ‘you belong!’ Education Week.

This article appears in the February 2022 issue of Kappan, Vol. 103, No. 5, pp. 8-12.

DENISE CLARK POPE is cofounder of Challenge Success and senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education. She is a coauthor of Overloaded and Underprepared: Strategies for Stronger Schools and Healthy, Successful Kids (Jossey-Bass, 2015).

SARAH MILES is the research and program director at Challenge Success, Stanford, CA. She is a coauthor, with Denise Pope and Maureen Brown, of Overloaded and Underprepared: Strategies for Stronger Schools and Healthy, Successful Kids (Jossey-Bass, 2015).